41062: Personal Glimpses of Gravir IV: Traditional Skills

An account of life in Gravir, by Calum Macinnes, 8 Gravir.

IV Crofting and Fishing Skills

Successful crofters need a wide range of skills. A crofter fisherman – and most heads of families in Gravir who were in this dual category – needed even more. I have already referred to the numerous skills needed by my father to construct our own, and his brother Murdo’s house. Add to these the boat and fishing skills required to be a successful fisherman in the days when the assistance of technology was minimal and you have a formidable array of the skills that had to be mastered: knowledge of weather forecasting, tidal currents, navigation maintenance of fishing gear and, when engines were installed in the sailing boats, knowledge of the maintenance and repair of these engines.

My father gave the engine of the Roselea, which he part owned along with his brothers Murdo and John and two others – Danaidh Dhomhnaill Mhurchaidh (Donald Matheson) and Calum Mairi (Malcolm Macleod) – an annual overhaul which necessitated dismantling and reassembling the engine – a difficult task for someone with no formal training in engineering.

He kept a basic set of tools in a chest at home. They were always maintained in a well-honed condition, usually with the assistance of a handle-operated sandstone sharpening wheel. This belonged to James Mackenzie, No 4 Gravir, (Seumas ‘An Thaboist). James was a polymath, not only in the well-read sense, but he was also exceptionally skilled in most manual trades. He built the only large-size fishing boat that was ever built in Gravir. The site of construction of this boat was to the east of the present day bridge, near the old Gravir school. My late uncle John told me that, as a young boy in the 1890s, he held the iron spikes for joining the boat’s planking to the ribs, while James hit them home with a sledge hammer. To launch the boat seaweed was placed under and along the keel on both sides to keep it upright and ease its passage. A pulley system provided the motive force. The boat fished for herring out of Gravir and Stornoway for many years.

When my brother Finlay and I were old enough to walk we wore kilts of plain, home-made tweed. If you ask what a boy wore under his kilt the answer is: nothing. This undoubtedly allowed maximum freedom of movement and it also allowed a parental hand to make easy contact with the buttocks, when behaviour required the administration of deserved punishment. I remember a very early case of the administration of such condign punishment for splashing with reckless abandon in the stream that flowed past my grandmother’s house. Trousers were used in the year of two before school enrolment. In fact the entire ensemble consisted of the trousers, a shirt and a jersey, in summer, with boots and stockings to supplement in winter.

During my pre-school years my father worked round the clock putting the finishing touches to the internal work on our house and uncle Murdo’s. Then he made the furniture. Although my memories of pre-school events are vague, I seem to recollect that his joinery tools and wood shavings were very much in evidence. The furniture was made of white pine. The Welsh dressers had pride of place, but he also made the beds, the chests of drawers, the stools and a good sturdy seis for each house. I sometimes wonder how he found time to participate in the herring fishing which was the sole means of earning a livelihood at that time. He was not then part owner of a fishing boat, but he worked on other boats that fished out of Gravir.

Before my schooldays began I remember waking up one night in one of the beds in the culaist – our ground floor bedroom. Five people were seated around our circular pedestal table: my father, uncle Murdo, uncle John, Malcolm Macleod (Calum Mairi) and Donald Matheson (Danaidh Dhomhnaill Mhurehaidh). They were having preliminary discussions on the proposed purchase of a fishing boat. The boat was in Barra and was being sold for 300. The sum of 60 per person was too much for them and they obtained a loan from one of the Stornoway fish-merchants – Bruce, I think. The loan was paid off in annual amounts until they had full ownership of it. They travelled to Barra on foot, taking ferries between the islands.

I can’t remember the arrival of the Roselea in Gravir. It was a fine, well-proportioned and sturdily built boat. It had a small engine and large mast and sail. The mast was removed and cut to shorten it, and its diameter was then decreased by assiduous use of that versatile carpenter’s tool, the adze. I remember the adze being used but my efforts to help with the work were discouraged by my father who regarded it as a tool that was too dangerous for small boys to handle! The sail was also made smaller to suit the shortened mast. The boat, when under sail in favourable sailing weather, was a fine sight.

The engine of the Roselea was rather small and soon after the boats arrival in Gravir, the crew bought an older boat which had a more powerful Kelvin paraffin engine. This boat was called the Frigate Bird. It was beached at the foot of croft No. 9. The engine was removed to replace the Roselea’s original engine and the hull was broken up, the planks used to provide cladding for sheds and the ribs to make fence posts. Several years ago sections of two ribs turned up in an unexpected setting. The sections were used to make a lintel for the front door of the house at No. 7 Glen, owned by my cousin Kenny Maclean. My father had helped build the house for Kenny’s late father, Neil Maclean. The wood, which was oak, had maintained its form and strength over the years.

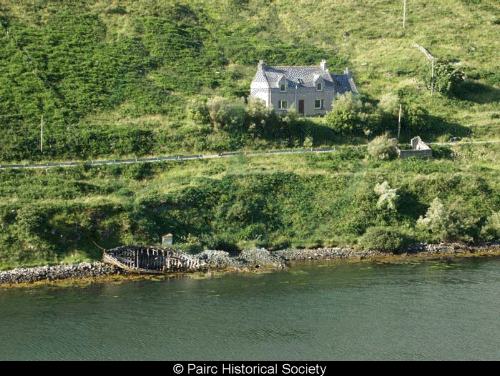

The Roselea is still in evidence: it was beached at high tide on the shore of croft No. 11, tenanted by the late Donald Matheson (Domhnall Dhanaidh) who had taken over as a crew member when his father, Danaidh Dhomhnaill Mhurchaidh, retired. I have the name plate of the Roselea in my possession and my late brother Donald John, named his new croft house at No. 8 Gravir after it. The comings and goings, and the fishing fortunes, of the Roselea were a source of perennial interest to us as we grew up in Gravir.

Iasg Ur – Fresh Fish

I have already referred to our fishing exploits during the summer months. In the winter months the adults took over. They used long lines: lion beag (small line) and lion mòr (long line). The former was not small in the sense of length; it had small hooks, closely spaced, say five hundred per line. The latter had bigger hooks, spaced about 2-3 fathoms apart. They were baited, usually with herring or mackerel strips, set at the mouth of the loch and left overnight if the weather was favourable. In the morning they were pulled in and they provided a great weight and diversity of fish: whiting, haddock, cod, skate, eel, gurnard and many other species.

Diet was almost exclusively boiled white fish at these times, but it was sometimes fried, sometimes salted, and sometimes salted and dried for later use. Cod roes, boiled, sliced and fried were a delicacy, as was ceann cropaig, a mixture of liver, oatmeal and seasoning, boiled in a large cod’s head. Diet in these pre-school days was simple but nutritious and although medical services were grossly inadequate the health of children was reasonably good if the scourge of tuberculosis (à chaitheamh) did not strike within a family. The disease was exceptionally virulent in the post World War One era.

A century and more earlier Loch Ghrabhair was teeming with even more fish and a novel method was used to capture them. A stone wall was built across an area of the foreshore which became exposed a low tide. The arrangement was called a ‘cairidh’ in Gaelic. When the tide came in, the top of the wall was submerged and the fish could swim over it. As the tide receded some of the fish were stranded behind the wall and they were left high and dry at the lowest point of the tide. They were simply picked up and taken home: an infallible way of ensuring a tasty dinner.

One wall was built across the loch about three hundred yards from its confluence with Grabhair river. Winter storms and powerful tidal bores (làgaraid) demolished the wall when it ceased to be maintained, but the stones from which it was built are still strewn across the loch and show the location of the wall. Two other cairidh sites on the south shore of the loch are also recognisable.

Fishing for other species required other methods. The cotton drift nets were used for herring; lobster pots – made with a wickerwork or willow frame on a wooden base and covered with netting – was used for lobsters and crabs; there were specialist nets for plaice, but in my experience they caught more crabs than plaice! and a conical net with a small mesh was used to fish for cuddies when they shoaled along the rocky shore at the end of the year. This net was called ‘tàbh’ in Gaelic. Buoys were made from sheepskins. The skins were salted or treated with alum, scraped to remove fat and wool and then stretched and dried. They were then attached to a wooden disc with twine. The disc had a blow-hole and a fixture for rope, it in, and when inflated and plugged they made good buoys that had a diameter of 15 inches or so.

Fishermen were superstitious and many of these superstitions continued to the earlier decades of this century. I remember a neighbour, John MacKenzie, No 34 Gravir – from whom my father bought his croft for 12 when John moved into a housing scheme for fisherman in Sandwick Park in the thirties – shouting angrily at my mother when she appeared at the end of our house wearing a red jersey as he left for work as a crew member of a Stornoway fishing boat. He was totally convinced that she would bring bad luck to him and the fishing boat!

Details

- Record Type:

- Story, Report or Tradition

- Type Of Story Report Tradition:

- Reminiscences

- Record Maintained by:

- CEP