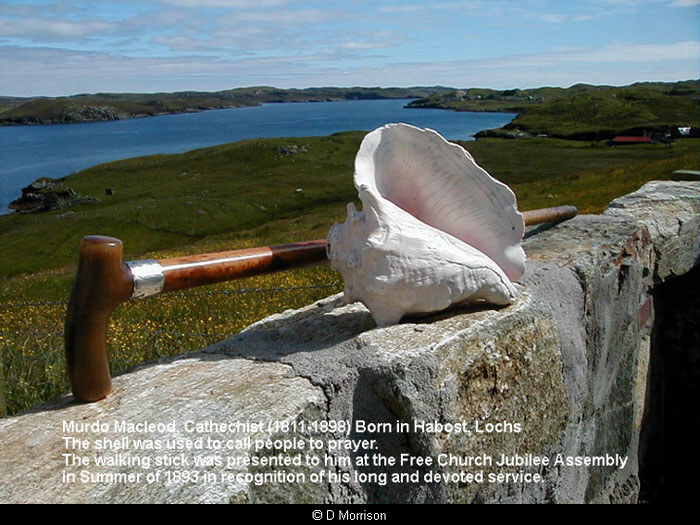

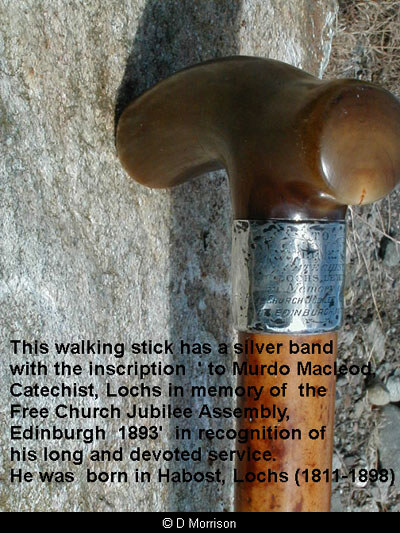

45991: Catechist Murdo Macleod, Lochs

An account of the life of Murdo Macleod, from "The Men of Lewis, Part 2" by the Rev Norman C. Macfarlane.

MURDO MACLEOD’S father was one of the early lights of Lochs. When the Rev. Malcolm Macritchie (Garrabost) was Gaelic school teacher in that parish he early one Sabbath day saw a man standing on a knoll in the village and crying upon the villagers in stentorian voice to arise from their beds and come to God’s House. Mr Macritchie asked the man where he wished them to go. To Keose Church, of course. But Keose Church, said Mr Macritchie, is as cold as an icehouse and no evangel-note sounds there. True, said the crier, but God’s Word is read there, and cold and dead though the minister be, he is the only one we have, and even there the way of life can be found. This Sabbath herald was Catechist Macleod’s father. The fire that burned in him reappeared in his son, and soon after the shouting on the knoll Murdo Macleod became a follower of the Lord, whom he served for 70 years with unflagging zeal.

(According to information held by Pairc Historical Society, it was not Murdo Macleod’s father (lan Ruadh Og) but his maternal grandfather (Alasdair Mac Tharmoid) who had the encounter with Rev. Mr Macritchie.)

In his young days he believed in ghosts, which is one of the occasional diseases that affect the Celt’s spiritual vision. After his conversion he struggled hard to get rid of this thraldom which haunted him like a dream. A kiln was a favourite resort of ghosts. Before entering, Murdo would thrust his hand under the door and call upon the ghost to take his hand and shake it. No kiln would he enter without this ritual. He was too virile a being to remain long in this bondage, and he soon swam into the light and liberty where ghosts cannot live. So, rapidly did he rise in public regard that he was elected and ordained an elder in his 32nd year. For the Highlands, that was a novelty. The Disruption had just taken place, and the young elder sprang into the saddle and rode into office straight to the end of his long life. Six years after his election as elder, a letter came addressed : "Mr Murdo Macleod, Catechist, Lochs." There was no such person in the parish, and Murdo Macleod would not open the letter. The letter created much uneasiness. Two worthy elders resolved to travel to Stornoway to ask the renowned Peggy Mackenzie to open it in their presence. She did so, to discover that it was the formal announcement of Murdo Macleod’s appointment as parish catechist. It fell on Murdo like a bolt from Elysium. He had never dreamt of such an honour, but his minister, the saintly Robert Finlayson, had dreamt of it, and wrote the authorities urging it. And now it came to pass. If ever a man was a predestinate catechist, it was Murdo Macleod. It is not easy to assess the value of his work. All through the island he was known as the Ceisdear Mor – Handsome in person and in service. Had there been a syndicate of catechists in the Lews he would have been unanimously pressed into the chair. Probably no royaller compliment could be paid him, for the Lews had a set of rare and marked catechists. He was their uncrowned king. In Lochs he worked under Robert Finlayson, John Macrae, George Lewis Campbell, Hector Cameron and John Macdougall as ministers, and his viceroyalty was extensive and supremely successful. He had a keen eye for human nature, both in its shirt sleeves and in its various garb, and his strong sense of humour added a relish. Once when catechising he asked an old man to name any one character in the Old Testament. "Oh, Catechist, your own grandfather was the only one I can *remember." The Catechist’s sense of solemnity was bankrupt in a moment, and he roared in one of his wholesome outbursts.

The Catechist became an ardent temperance reformer and threw all his influence into the teetotal scale. How cordially he would have seconded the speech of the man who was asked, "Are you going to the burying of the innkeeper ?’ "No, I am not, but I quite approve !" Donald John Martin, that great apostle of temperance in the Lews, once persuaded the minister and catechist of Lochs to adopt unfermented wine for the Communion. Mr Macdougall ordered it, and informed the Session. They rose in arms. The thing would empty the Sacrament of all its meaning. The Catechist was big and broad-minded. To him the validity of the Sacrament did not rest on the external or accidental. A small supply of Old Port was ordered, and the Catechist secretly mixed the port and the unfermented together. When asked after the "tables" what came over the unfermented supply, he laughingly remarked that it had passed into the interior calabash of all the communicants, and was now simmering in their brain! He thus made prejudice to melt under his wise touch.

There were always some who trusted him in all circumstances. They were those who would sooner be wrong with Plato than right with Aristotle. But when he opened his batteries against blind and stupid conservatism, he usually dashed it to flinders. His moral vision was singularly free from astigmatism, and he saw things in their right focus. His opponents found it difficult to discover his Achilles heel, although, of course, like all humans, he had that spot of vulnerability. He was great in prayer, and he had many answers, of the notable and Providential kind. Once when the wolf hung around his door, he left his house with the kettle on the hob singing its song of hope.

He went straight to the Manse and asked for the letter which Mr Finlayson received for him. Mr Finlayson did not remember any such letter. "That’s strange," said the Catechist, "for I had an assurance in prayer today that the minister had a letter for me." Mrs Finlayson went to search and found that her absent-minded husband had received a letter addressed to the Catechist. It contained a pound note. The wolf fled, and the song of the kettle was transmuted into a happy brew ! There was other sweet singing in the house that day. Another time he got a boll of meal in Stornoway, and he said he hoped he would be able to pay it before it was all used up. Some weeks passed and the meal-chest became empty like the Sarepta barrel. He set off to Stornoway and brokenly poured out his heart to God on the way. He had no sooner entered the town when an utter stranger approached, and said, "Take that; I’m ordered to give it you," and disappeared. In the envelope was a five pound note. He never knew who the donor was.

Once again he was on a double errand. He left home for the Sacrament celebration at Ness, and also en route to pay his croft rent at Stornoway. The rent was 3 17s. He had that, and not a farthing more. The tempter came to him, as a very considerate Satan, and urged him to remember God’s work and hold back one shilling for the collections of the Ness Communion. He said, "Get thee behind me, thou false tempter." Soon after he saw a wild goose, took a stone, and with sure aim killed the bird. "Ah", he said, "I’ll get collections now, and tobacco to boot." He carried the goose to Stornoway and was offered for it more than he required. He declined the offered price, and would only take the value of one ounce of his favourite weed and a copper for each Ness service. The Rev. D. J. Martin rolled this story as a relishable morsel under his tongue, and never ceased to chaff the Catechist over the providential goose! Many a burst of Martinesque laughter struck the walls as the story was trotted out again and again in all its detail. The Catechist had many gladiatorial encounters with Mr Martin. He used to say Mr Martin’s preaching was very good when it was good, but he was often enough a poor one-legged preacher. The Catechist was candid, and never sugary. His descriptive gift was very marked, and he could hit off a preacher and Question-speaker in a luminous phrase. He heard Martin’s striking sermon on "Not far from the Kingdom" and urged him to go and preach it in every church in the island. It was so supremely good.

In appearance Catechist Macleod was a big Rhomboid, with a strong, round full face and a round big head. There was nobody else in the Lews exactly like him, and if the cartoonists had to present him variously, it would be difficult to mistake him under all guises, just as Mr Gladstone could not be mistaken whether as woodman or Chancellor or bookworm. There was in Catechist Macleod, as in Mr Gladstone, something regnant, a solar light that commanded. He was careful of his personal appearance. Casually he had tea once at a friend’s house. After the tea came a service in the school which he was to conduct. He said he must go home and shave before the service. The friend remonstrated and said it was utterly unnecessary. He was quite presentable. All in the house urged the same. But not all the king’s horses and all the kings’s men could make him go to the schoolhouse unshaven. He said he could not enjoy a service, if he did not honour it by perfect tidiness.

His was a singularly tuneful soul. He was nearly all his life a precentor, and his leading of the praise made people take the stoppers out of their ears. His voice was full of colour. He had a quick, true ear. He once heard one of Sankey’s hymns sung. From that moment it sang itself within his ear and on his tongue. He was constantly humming or singing, and he made the air around him melodious. He seldom visited the sombre fields of Ecclesiastes where such pessimists as read Scripture luxuriate, but the Song of Solomon was his canticle, and the majestic passages of Isaiah he chanted in a metre of his own. He was a real poet, but did not commit to paper any of the makings of his mind. His son Murdo inherited the poetic gift, and he produced the popular anthem of the Lews Eilean-an-fhraoich. In the early years before his teens, this well-known son gave signs of the divine afflatus, and the Catechist could say as Thackeray said of his daughter’s first literary production, "It moistened my paternal spectacles."

When the union of the Churches was in the air he stood up for it with unfailing verve, and said of some who went to an anti-Union gathering in the Schoolhouse that if they had gone to that school in their earlier life they would not be found going there now ! He stood as on an Alp and saw clearly and far. He had a kind of pleasure in bringing to earth those who walked on high stilts.

At the age of 25 he married Ann Morrison, of Gravir, sister of Hector Morrison, elder, one of the Gravir trio. Her refined appearance rises to my eye. She was a bit of Dresden china, and was the happy mother of eight sons and three daughters. His son John died in early youth, and I remember the strange rumour that the Corp Cre found in a burn in Lochs was meant to represent him. So recently as 50 years ago, and less, was the Corp Cre, which was studded all over with pins, an article of creed in some of the slower Lews minds. Catechist Macleod died in January, 1898, having attained the age of 87. His mental faculties had never come to autumn sere and yellow. His visits in the houses of Lochs left a preciousness that lingered until he came again. He was a great catechist and a great man, the sort that St. Paul would often have mentioned in his despatches from the front. Lewismen never cease to be proud of having known and heard this distinguished son of their island.

Details

- Record Type:

- Story, Report or Tradition

- Type Of Story Report Tradition:

- Extract From Book

- Record Maintained by:

- CEP