718: Personal Glimpses of Gravir I: The Village

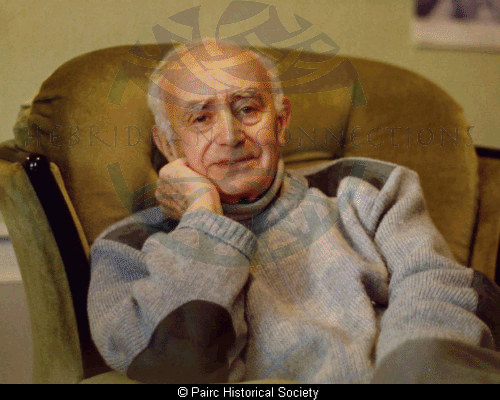

An account of life in Gravir, by Calum Macinnes, 8 Gravir.

I The Village

The village is Gravir. It straddles the first mile or so of a fiord-like sea loch, some dozen miles south of Stornoway, on the east coast of Lewis. The loch, which is almost four miles long, is referred to in Ordinance Survey maps as Loch Odhairn. Its proper Gaelic spelling is Iuthairn, the word meaning ‘hell’ in English. The indifferent spelling of Gaelic names in Ordinance Survey maps is explained by the fact that cartographers who drew these maps at the beginning of the last century were monoglot English speakers who listened to the Gaelic sounds of the words and transcribed then in accordance with the rules of English orthography.

I don’t like the name Loch Iuthairn applied to our picturesque sea-loch, but I cannot deny its appropriateness when an east or northeast gale is blowing and the roiling sea builds up against the massive bulk of Creag Mhor – the main precipice of Kebock Head – and the smaller mass of Sron Liath. I can imagine the frightening effect the turbulent sea and lowering clouds would have on the crews of sailing ships of long ago when they were forced to enter the inner reaches of the loch to seek shelter from the fury of easterly gales. Nevertheless, I don’t like the name applied to a loch that has given me so much pleasure during my life and I prefer to call it Loch Ghrabhair.

The village name is of Norse origin, being translated as ‘pit, hollow or grave’ in recognition of the steep nature of the slopes of the land bordering the loch and also the steep slopes of the glen which carries a fast-flowing river into the narrow, inner end of the loch. The township of Gravir consists of 44 crofts; most of them on the northern side of the loch, and its satellite township of Glen Gravir – bought from the Estate by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries in the early twenties to accommodate families that did not have exclusive use of land in Gravir – has 15 holdings.

The two townships share a church – the Free Church – and a post-office; they also share a cemetery, sheltered housing, and a care unit for elderly and infirm residents with the other villages of South Lochs or Pairc which is the name given to the district in electoral rolls.

Gravir is, and always has been, the centre of my universe.

The Past

Thirteen thousand years ago, Gravir – like the rest of Lewis – was in the grip of the last Ice Age. Evidence of the Ice Age was left behind when the ice moved and melted: boulder clay, or till, was left behind in many places along the side of the glen; gravel (morghan in Gaelic) was also left behind in some places; stray boulders, some very large, were carried along by the moving ice and deposited in the position they occupied when the ice melted; the glen was deepened and lochs formed by the weight and gouging action of the great mass of ice.

Excluding weathering over the years, the growth of vegetation and the formation of peat in some places, the panoramic configuration of Gravir is much as it was at the end of the last Ice Age. Nothing is known of Gravir in the pre-historic era but evidence of the Norse occupation in the early historical period – from the 9th to the 12th centuries – is perpetuated in the place-names. For example, Magne Caftedal, in his ‘The Village Names of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides’, mentions the following South Lochs villages (the present Ordinance Survey Map names are given in brackets): Grafir (Gravir); Sildanes (Shildinish); Habolstaor (Habost); Hjartsetr (Kershader); Mararvik (Marvig); and Kolbjarnarbolstaor (Calbost).

From the mid-seventeenth century to the early nineteenth century, settlements were established in various parts of South Lochs. This was followed, in the second, third and fourth decades of the nineteenth century, by clearances and the adoption of large-scale sheep farming. After this, thriving fishing townships, including Gravir, led to an increase in population until 1911, when the population of the district was at its maximum.

Beginnings

At the end of 1918, on the cessation of the First World War hostilities, my father, Angus MacInnes (Aonghas Fhionnlaidh Iain Ruaidh) returned to Gravir. He had seen active service as a leading seaman in the Royal Naval Reserve during the war. He lived on croft No 8 Gravir at the end of Loch Ghrabhair, about five hundred yards from the village school which was built in the early eighties of last century. Shortly after his return home he married my mother, Marion MacRitchie (Mor Chaluim Choinnich) from the adjacent croft, No 9 Gravir. They were married in Stornoway. Afterwards, they walked to Crossbost, crossed Loch Erisort by rowing boat to Cromore and walked from Cromore to Gravir. The road from Balallan had not been built at that time and so it was not possible to travel to Gravir by vehicular or horse-drawn transport.

They set up house in the old barn at No 8. My father had carried out some basic renovations: he had built a wooden partition to form a bedroom and made some essential items of furniture, including the box bed with its palliasse filled with oat straw and warm home-made blankets. The fabric of the barn was unchanged – thick walls with clay and gravel filling between the inner and outer stonewalls, a good thick thatched roof and two small one-pane windows to let in some light. It was a small, cosy and comfortable home. My elder brother, Finlay, was born in September 1919. I followed on 13 December 1920.

I have often heard a person who was careless about closing doors being asked sarcastically: ‘Were you born in a barn?’ I could answer truthfully: ‘Yes.’

Some people have a phobia in the form of an irrational aversion to the number 13. I haven’t. If I had, I would surely suffer from a double dose of it because I now live at 13 Glen Gravir. It would be embarrassing if I had to tell people that I suffered, among other ailments, from triskaidekaphobia!

By all accounts I was a fractious baby and I cried, very often at night, for no apparent reason. My mother told me that she often felt like throwing me to the other end of the bed and leaving me there. My behaviour was the antithesis of my brother Finlay’s, who was a placid, cheerful child.

During this time, my father was building two semi-detached houses, one for us and one for his brother Murdo, from the materials obtained from a wooden corrugated iron hut, used by servicemen in Stornoway during the war. It cost 100.

Details

- Record Type:

- Story, Report or Tradition

- Type Of Story Report Tradition:

- Reminiscences

- Record Maintained by:

- CEP